Remembering Mataji

(Mrs. Illaichidevi Goenka, January 18, 1929–January 5, 2016)

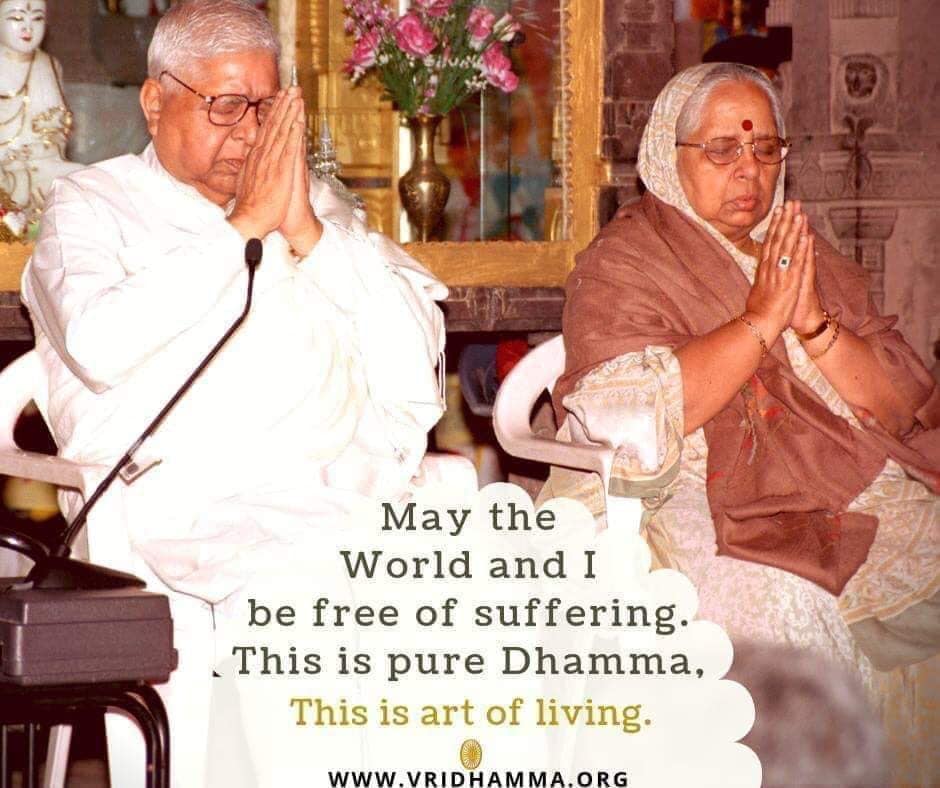

From the early 1970s, participants in Vipassana courses were accustomed to see by Goenkaji’s side his wife, Illaichidevi, known as Mataji (“Respected Mother” in Hindi).

Most of the Westerners quickly realized that they did not share a common language with her.

Occasionally, however, someone was curious enough to ask politely what her role was.

Goenkaji would usually laugh and respond for her, saying that she was there to meditate and give mettā.

That answer was enough to satisfy the questioner’s curiosity, but much more could be said.

Certainly, Mataji was Goenkaji’s wife, a comforting presence meditating next to him. But she was also his life partner, and his partner in the Dhamma mission that he had undertaken.

Early years to the outbreak of war.

Their lives had been intertwined for decades. Mataji had been born into a Rajasthani family living next door to the Goenka family in Mandalay, the old capital of Myanmar.

In the traditional way, the families arranged for the two to marry, in January 1942.

At the time, Goenkaji was nearing his 18th birthday, while Mataji was five to six years younger.

This was entirely usual in that time and that community.

Nevertheless, Goenkaji was reluctant to marry someone so much younger than himself.

For years afterward he felt ashamed that, because of him, Mataji had to leave behind the innocence of childhood and embark on adult life at an early age.

The time of their marriage coincided with a grave moment in world history.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The next day, they began attacks throughout East and Southeast Asia. Hong Kong fell on December 25, and Singapore within a few weeks. As the wedding guests celebrated in Mandalay, Myanmar was already under assault.

The onslaught came from the south, with the initial objective of overrunning the port city of Yangon. Very soon, there was virtually no way to escape the Japanese advance except by traveling overland to the north and west. From Mandalay in Upper Myanmar to British-controlled territory in India, the distance was relatively short. Still, the route was arduous, leading through the Naga Hills, traversing jungle and high mountain passes before reaching northeast India.

Many thousands of Indian residents of Myanmar decided to flee for safety to their ancestral homeland. The railway was out of operation. On some stretches, buses were brought into service. Otherwise, the refugees traveled by ferry or paddleboat, cart, bus or the rare automobile, or else on foot. All along the way, priority went to the retreating British forces. Sometimes, the colonial authorities handed out rations and arranged for tents; at other times, civilians had to find their own food and shelter. Many died along the route from hunger, disease or exhaustion. One of the most notable exoduses of the Second World War, it has been nearly forgotten by history.

Among the thousands of people displaced by the conflict, Goenkaji led a small band of family members. Mataji traveled separately with her own family. Much later, Goenkaji said that when they arrived in India, he was the only member of his family able to stand on his own feet.

Return to Myanmar and encounter with Vipassana.

The war years were spent in Rajasthan and then in south India. Once peace came and order was restored, however, Goenkaji and Mataji returned with his adoptive parents to Myanmar, settling in the capital, Yangon.

There he embarked anew on his business career and also became involved in community service. Meanwhile, Mataji looked after their children and helped to run the household. With 25 to 30 family members living together, it was a job that called for tact, patience and hard work.

Goenkaji often told the story of how he achieved business success in the postwar years, and how the resulting tensions eventually led him to join a Vipassana course in 1955, under the guidance of Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

At the end of his first course, Mataji went to the meditation center and met Sayagyi, who took the opportunity to teach her Anapana.

Three or four years later, she had the opportunity to join a 10-day course herself.

Sayagyi spoke very limited Hindi, and Mataji did not know Burmese or English. Despite this, she recalled, there was no real language barrier: “Sayagyi didn’t talk much. By gestures he would ask and by gestures I could reply, and that was more than enough.”

Meanwhile, Vipassana was working a transformation in Goenkaji. As he often mentioned, he was relieved of the tension that gave rise to his migraine headaches. And there were other benefits. He had been a very hot-tempered person, quick to anger. He used to say that when he returned to his home and entered the front door, his sons would run out the back. Now the tendency to anger was greatly diminished, and he found that he could easily control his temper.

His life became more peaceful, and his relations improved with everyone around him. Meditation strengthened his relationship with Mataji, drawing them closer together.

Teaching years.

In 1969, Goenkaji left Myanmar to begin teaching Vipassana in India.

In the first two years, Mataji remained behind to look after the family. During that time she frequently went to Sayagyi’s center, and she said that he gave her more attention than ever before: “He knew that I was separated from Goenkaji, and he was as concerned about me as any parent would be. I would go to his center and meditate, and then sit and talk a little with Sayagyi, and then I would feel so much better, very relaxed. There was so much mettā in him. I felt it at that time particularly.”

She remembered, “Sayagyi would very often say to me, ‘You have to work very hard! You have to do a lot of work, you have to work so much!’ … I wondered: Why was Sayagyi telling me that I had to continue to do domestic chores throughout my life? … I didn’t know what Sayagyi meant.”

Of course, Sayagyi had in mind something other than domestic work.

In May 1970, Shriram Taparia and his wife Suman paid a visit to Yangon. They were the only students of Goenkaji to meet Sayagyi before he passed away. They also talked with Mataji and told her firsthand about Goenkaji’s success in spreading Vipassana in India. Not long after, Mataji wrote to him that she hoped to be able to join him soon.

The following January, in 1971, Sayagyi passed away. Like all his students, Mataji keenly felt the loss. Once, while sitting at the center, she recalled, “I felt if there is no Sayagyi, there is no center, there is no use in my coming here. Then I had the feeling as if Sayagyi were standing near me; but when I opened my eyes, there was nothing. It was just a feeling inside, feeling his presence.”

Within less than a year, Mataji was in India. Although she could not be at every course conducted by Goenkaji, she joined him as often as she could. Through the years, she shared the joys and challenges of Goenkaji’s mission, from the spartan conditions in the early days in India to the long lineups for private interviews on the first courses in the West.

An example of devotion.

In December 1981, Goenkaji appointed the first assistant teachers. In meetings with the handful he had named, he explained to them what they would have to do.

Naturally the talk turned to how Sayagyi had trained him and Mataji, and how the two supported each other.

Goenkaji repeated what he had often said publicly: Mataji’s mettā gave support to all the course participants. In addition, her presence made it easier for Goenkaji to teach women.

In the early 1970s, he was in the full vigor of life, and in a very few cases women became attracted to him personally.

With Mataji by his side, such a problem was far less likely to occur. He called her his protection. She also provided reassurance to women from traditional homes who were unaccustomed to mixing in public: They felt more at ease when they could talk with her, or simply when they saw her sitting on the teachers’ dais.

But Goenkaji explained that Mataji had a more direct role in the teaching.

She too had been trained by Sayagyi.

Often, when she and Goenkaji meditated with students, they would return to their room and discuss their impressions. In later years, they did the same after viewing a prospective site for a new center. Goenkaji greatly valued her input, even though she always gave it privately.

Goenkaji and Mataji became models for those first assistant teachers and for all who came after, despite differences of culture and upbringing.

The most important lesson they gave was of humility and selfless service. It is a lesson worth learning over and over again.

In the late 1990s, Goenkaji gave a talk to assistant teachers, speaking as usual in two languages. In English, he referred to the need to start preparing for his absence within a few years. In Hindi, he used much vaguer language, perhaps with the intention of not worrying Mataji.

Nevertheless, the years were passing, inevitably bringing with them sickness, old age and death.

Mataji remained by his side, and she was with Goenkaji in September 2013, when he breathed his last.

After a lifetime together, she faced the moment with fortitude and equanimity.

This was a time of great danger to the Dhamma mission, when differences resurfaced that Goenkaji had been able to bridge.

With great dignity, Mataji encouraged all meditators to set aside disagreements and work together in harmony.

Long ago, in 1992, she said, “I don’t speak much because I am very aware of the fact that nothing wrong, nothing which is not truth, should come from me. I am very aware of this fact. Even from my childhood it has been my nature to speak less about matters involving many people. It is better to watch, better to be watchful than to be actively participating, talking.”

By her own example, Mataji showed the value of silent observation, of quiet devotion, of good will towards all. It is an example that will long give inspiration to others.

May she be peaceful, happy and liberated!

http://news.dhamma.org/2016/04/remembering-mataji/

———————–

असीम कृतज्ञता

उपकार उन सभी आचार्यो का है जिन्होंने लौकिक विद्या दी या लोकोत्तर विद्या दी।

जिससे इस मनुष्य जीवन का सफल उपयोग किया जा सके।उनके प्रति असीम कृतज्ञता का भाव रहना चाहिये। जिन गुरुजनो ने केवल लौकिक विद्या ही दी जिससे की जीवनयापन में सुविधा मिली उनका उपकार तो महान है ही परंतु जिन्होंने लोकोत्तर विद्या दी उनके उपकार की कोई सीमा नही।

———————

Mataji

Since 1969, Goenkaji and his wife are conducting Vipassana courses.

Mrs Goenka, known fondly as ‘Mataji’ (meaning ‘respected mother’), is also a Principal Teacher and a distinguished student of Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

She has quietly supported and selflessly served in her husband’s mission of gratitude to their beloved teacher, Sayagyi U Ba Khin: how to serve more and more beings in benefiting from the liberating path of Vipassana.

(Principal Vipassana Teacher S N Goenka – http://www.vridhamma.org/Teachers-4)

http://www.vridhamma.org/

https://www.dhamma.org/en/courses/search

Nguồn: Paresh Gujarathi facebook

Link: https://www.facebook.com/GUJARATHI/posts/3694841267226201