MỘT VÀI SỰ KIỆN TRONG CUỘC ÐỜI THIỀN SƯ U BA KHIN

— S.N. Goenka kể lại

Con Người Chính Trực Trong Thời Loạn Cũng Như Thời Bình

Tháng 2, 1942, quân xâm lăng của đế quốc Nhật đã chiếm Yangon, và đang tiến về Mandalay, một thành phố ở miền trung Myanma. Không quân Nhật bắt đầu oanh kích thành phố, phá huỷ một nhà ga xe lửa tại đây.

Lúc này Sayagyi đang ở Mandalay trong chức vụ Cán bộ Kế toán đường sắt, chịu trách nhiệm quản lí toàn bộ ngân quĩ đường sắt. Sau khi cuộc oanh kích chấm dứt, ông chạy ngay tới nhà ga vừa bị tàn phá, lùng sục trong đống đổ nát, và thấy két sắt vẫn còn y nguyên không hề hấn. Vì có chìa khóa của két sắt, ông mở két và lấy ra toàn bộ số tiền trong đó — một số tiền rất lớn.

Phải làm gì với số tiền này bây giờ? U Ba Khin cảm thấy rất hoang mang. Chính quyền Anh đã chạy trốn cuộc tấn công như vũ bão của quân Nhật. Mandalay lúc đó là một “đất vô chủ” giữa hai quân đội giao tranh — một thành phố vô chính phủ. Tất nhiên, U Ba Khin có thể giữ số tiền cho mình, vì ngoài ông không có người nào chịu trách nhiệm cao hơn. Dù sao, chính quyền thực dân Anh lúc này là kẻ thua trận đang chạy trốn nên họ không thể có quyền nào đối với số tiền này. Và giành lại số tiền này của họ có thể được coi là một hành động ái quốc. Hơn nữa, lúc đó U Ba Khin rất cần tiền, vì cô con gái út của ông đang lâm bệnh nặng, và các chi tiêu của ông quá nặng nề ông không thể nào kham nổi. Thế nhưng U Ba Khin đã không hề có chút ý tƣởng nào về việc giành giật tiền của nhà nước để bỏ vào túi riêng của mình. Ông đã quyết định, bổn phận của ông là chuyển lại số tiền này cho các viên chức chính quyền mặc dù họ đang chạy trốn khỏi nước.

Từ Mandalay quân Anh bỏ chạy tán loạn. Các cán bộ đường sắt lúc đầu chạy đến Maymyo, với hi vọng tìm đường qua Trung Hoa rồi từ đó đáp máy bay qua Ấn Ðộ. Sayagyi U Ba Khin không chắc mình có thể bắt kịp họ trong cuộc chạy trốn của họ. Dù sao ông vẫn phải thử xem sao. Ông thuê một chiếc Jeep taxi và đi mất ba giờ để đến Maymyo. Tới nơi, ông thấy người Anh vẫn còn ở thành phố này. Ông đi tìm cấp trên của ông và trao lại số tiền nói trên, rồi thở phào nhẹ nhõm vì đã trút đƣợc gánh nặng của mình.

Chỉ sau khi đã giao nộp tiền xong xuôi, ông mới nói, “Thưa ngài, bây giờ tôi được lãnh lương của mình trong tháng này, và tiền xe cộ để đến đây chứ?” U Ba Khin là con người như thế đó, một con người công minh chính trực, một con người đạo đức liêm khiết, một con người Giáo pháp.

Giáo Pháp Làm Biến Ðổi Một Bộ Trong Chính Quyền

Bằng cách đưa việc thực hành Thiền Quán đến với các cán bộ và nhân viên của văn phòng Kế toán trưởng Miến Ðiện, Sayagyi U Ba Khin đã mang lại một sự cải thiện to lớn trong văn phòng nhà nƣớc này. Vị Thủ tướng lúc đó là U Nu, một con ngƣời liêm khiết và muốn toàn thể guồng máy chính phủ trong đất nước phải hoàn toàn loại trừ được nạn tham ô và vô hiệu quả. Một trong những bộ quan trọng nhất của chính phủ lúc bấy giờ là Bộ Thị trƣờng Nông nghiệp nhà nƣớc hoạt động rất kém cỏi. Bộ này có trách nhiệm thu mua lúa và các nông sản khác của nông dân rồi xay thành gạo để xuất khẩu với số lượng lớn.

Vào thời thực dân, toàn bộ việc kinh doanh xuất khẩu nằm trong tay các thƣơng gia Anh và Ấn Ðộ. Sau khi Myanma giành độc lập, Bộ Thị trƣờng Nông nghiệp đã đảm nhận trách nhiệm này. Ða số cán bộ và nhân viên của Bộ đều ít kinh nghiệm. Mặc dù tổng lợi tức của ngành thương mại này rất lớn, nhƣng Bộ gần như lúc nào cũng trong tình trạng thâm thủng ngân sách. Không có một hệ thống kế toán thích đáng; tính vô hiệu quả và tham nhũng lan rộng. Các viên chức của Bộ cấu kết với những nhà máy xay lúa và những thương gia nước ngoài để chiếm đoạt những món tiền khổng lồ của nhà nước. Thêm vào đó, phương pháp trữ kho và vận chuyển kém cỏi đã tạo ra những thất thoát và thiệt hại lớn.

Thủ tướng thiết lập một uỷ ban đều do U Ba Khin đứng đầu để lo việc điều tra những vụ việc của Bộ này. Báo cáo của uỷ ban này đã phơi bày một cách không sợ hãi toàn bộ mạng lưới tham ô và kém hiệu quả của Bộ. Cương quyết có hành động dứt khoát, Thủ tướng yêu cầu U Ba Khin đảm nhận chức vụ Phó chủ tịch của Bộ. Nhưng U Ba Khin do dự đảm nhận trách nhiệm cải tổ bộ này, trừ khi ông có quyền hành rõ ràng để có những biện pháp cần thiết. Hiểu được vấn đề, thủ tướng đã bổ nhiệm ông làm Chủ tịch Bộ Thị trƣờng, một chức vụ thường do Bộ trưởng Thương mại nắm giữ. Người ta thường cho rằng chức vụ này có một lực bẩy chính trị rất lớn, thế mà giờ đây nó lại được trao cho một công chức liêm khiết.

Khi thủ tướng loan báo ý định bổ nhiệm này, các viên chức của bộ rất lo ngại con người đã từng phanh phui những hành động sai trái của họ giờ đây sẽ trở thành cấp trên của họ. Họ tuyên bố sẽ đình công nếu thủ tướng xác nhận việc bổ nhiệm này. Thủ tướng trả lời ông sẽ không xét lại quyết định bổ nhiệm, vì ông biết chỉ có U Ba Khin là ngƣời có thể đảm đương công việc. Và toàn thể các viên chức cán bộ đã đình công. Thế là U Ba Khin phải đảm nhận trách nhiệm trong một bộ mà toàn thể các viên chức cán bộ đều đình công, chỉ có những nhân viên thƣ lại và những công chức xoàng là tiếp tục làm việc nhƣ bình thường.

Sayagyi U Ba Khin vẫn cƣơng quyết trước những đòi hỏi vô lí của những ngƣời đình công. Ông tiếp tục công việc điều hành với vỏn vẹn chỉ có ban nhân viên thư lại. Sau nhiều tuần lễ, nhóm cán bộ đình công nhận thấy Sayagyi không chịu sức ép của họ, nên họ đành đầu hàng vô điều kiện và trở về với chức vụ của mình.

Sau khi thiết lập được uy tín của mình, bây giờ Sayagyi bắt đầu không thay đổi toàn thể bầu khí và lề lối làm việc của Bộ, với một lòng yêu thương và thông cảm tột độ. Giờ đây nhiều cán bộ đã theo dự các lớp thiền định dưới sự hướng dẫn của ông. Trong hai năm ông giữ chức Chủ tịch, Bộ đã đạt tới những mức kỉ lục về xuất khẩu và lợi nhuận; và đã đạt tới mức hiệu quả cao nhất chưa từng thấy trong việc giảm thiểu những thất thoát và thiệt hại.

Thời đó người ta đã quá quen với chuyện các cán bộ và thậm chí Chủ tịch của Bộ Thị trƣờng tích lũy tài sản bằng những cách bất hợp pháp trong nhiệm kì của họ. Nhưng U Ba Khin không bao giờ dung túng cho thói quen này. Ðể ngăn ngừa bị mua chuộc, ông từ chối tiếp xúc với các nhà buôn và các chủ nhà máy xay, ngoại trừ khi có công tác chính thức, và chỉ tiếp xúc tại văn phòng chứ không ở nhà riêng của ông.

Một lần kia, có một thương gia đã xin Bộ chấp thuận đề nghị để họ cung cấp một lượng bao bì rất lớn. Theo thông lệ, thương gia này đã chuẩn bị kèm theo đơn xin của mình một “khoản đóng góp” tư cho một cán bộ quan trọng của Bộ. Ðể chắc ăn, thƣơng gia này quyết định đến gặp chính vị Chủ tịch. Ông đến nhà của Sayagyi, mang theo một khoản tiền rất lớn để làm quà. Trong lúc trò chuyện, khi bắt đầu thấy có gợi ý về sự mua chuộc, Sayagyi sửng sốt rõ ràng và không thể che giấu sự khinh bỉ của mình trƣớc việc làm đó. Bị bắt tại trận, ngƣời thƣơng gia kia đã phải chữa lỗi bằng cách nói rằng món tiền không phải có ý biếu Sayagyi mà là muốn dành cho trung tâm thiền của ông. Nhưng ông nói rõ cho người thƣơng gia này biết trung tâm của ông không bao giờ đón nhận quà tặng từ những người không phải là thiền sinh, ông đuổi người thương gia này ra khỏi nhà, và bảo người này phải biết ơn ông vì ông chƣa gọi cảnh sát.

Trong thực tế, để ngăn ngừa mọi hành vi mua chuộc, Sayagyi đã cho mọi ngƣời biết ông không bao giờ chấp nhận một món quà nào dù lớn hay nhỏ. Một lần kia vào dịp lễ sinh nhật ông, một nhân viên cấp dƣới đã mang đến nhà ông một gói quà trong lúc Sayagyi vắng nhà: một chiếc longyi lụa, là một loại áo sa-rông đắt tiền mà ngƣời ta rất thích mặc. Vào cuối ngày làm việc, ông cho họp ban nhân viên. Ông khiển trách nặng lời ngƣời nhân viên kia đã coi thƣờng lệnh của ông. Sau đo,ù ông mang chiếc sa-rông bán đấu giá rồi bỏ số tiền ấy vào quĩ phúc lợi chung của nhân viên. Một lần khác, ông cũng có một biện pháp tƣơng tự khi đƣợc biếu một giỏ trái cây. Ông luôn luôn ý tứ không cho phép ai mua chuộc mình bằng những món quà dù lớn hay nhỏ.

Con ngƣời U Ba Khin là nhƣ thế — một con ngƣời nguyên tắc rất mạnh không gì có thể làm ông chao đảo. Quyết tâm của ông nhằm nêu một tấm gƣơng về ngƣời cán bộ liêm khiết đã khiến ông phải đi ngƣợc lại rất nhiều thói lệ phổ biến vào thời đó trong công việc hành chánh. Thế nhƣng đối với ông, sự toàn vẹn đạo đức và quyết tâm phục vụ Giáo pháp luôn là trên hết.

Dịu Dàng Như Cánh Hoa Hồng, Cứng Rắn Như Kim Cƣơng

Một vị thánh đầy tình thƣơng và lòng trắc ẩn, ngài có một quả tim mềm mỏng nhƣ cánh hoa hồng. Nhƣng khi đụng tới bổn phận, ngài trở nên cứng rắn nhƣ đá kim cƣơng. Cả hai nhân đức này đƣợc thể hiện tùy mỗi hoàn cảnh khác nhau trong đời sống của Sayagyi. Sau đây là một ít sự kiện minh chứng điều đó.

Khi Myanma giành độc lập từ tay nƣớc Anh năm 1948, chính phủ quốc gia vừa mới thành lập đã phải đối diện ngay với một cơn khủng hoảng. Trên khắp đất nƣớc, những ngƣời theo những ý thức hệ khác nhau đều chống đối chính phủ: một số thuộc phe cộng sản, một số thuộc phe xã hội, một số thuộc những nhóm địa phƣơng chủ trƣơng li khai. Nhóm ngƣời nổi loạn không thiếu gì vũ khí đạn dƣợc, vì trong Thế chiến II cả quân Nhật lẫn quân Ðồng minh đều phân phát không các vũ khí và đạn dƣợc để thu hút thanh niên Miến về phe họ. Quân nổi loạn dấy lên khắp nơi khiến cho chính phủ mới thành lập không thể nào đối phó với cơn khủng hoảng. Chẳng bao lâu sau, quân nổi loạn thắng thế, nhƣng mỗi nhóm theo một cƣơng lĩnh và khẩu hiệu riêng của mình, tạo nên một tình trạng hỗn loạn vô chính phủ trên khắp đất nƣớc. Mỗi phe nhóm với cƣơng lĩnh riêng của mình đều chiếm đóng và cai trị một phần lãnh thổ của đất nƣớc.

Thế là đến thời kì chính phủ liên bang Miến Ðiện trên thực tế chỉ còn là chính quyền của riêng thành phố Yangon. Không bao lâu sau, thậm chí vùng lãnh thổ nhỏ nhoi này cũng gặp nguy hiểm khi một nhóm nổi loạn bắt đầu tiến vào cửa thành phố và chiếm đóng một ngôi làng cách xa thành phố chỉ chừng mƣơi dặm. Cả đất nƣớc không còn nơi nào có luật pháp; sự tồn tại của chính quyền liên bang lúc này nhƣ sợi chỉ treo ngàn cân. Nếu chính quyền ở Yangon sụp đổ, Liên Bang Myanma sẽ bị phân chia thành những phe nhóm tranh giành nhau. Chính quyền đã bị suy yếu, quân đội cũng suy yếu — nhƣng biết làm thế nào? Xem ra không có lối thoát nào cả.

Sayagyi hết lòng tận tụy với đất nƣớc, và khao khát sự hòa hợp và thịnh vƣợng cho Myanma, nhƣng ông có thể làm đƣợc gì? Ông chỉ có một sức mạnh duy nhất là Giáo pháp. Vì vậy, có khi ông đi đến dinh Thủ tƣớng và thực hành Tâm từ (mettà) phƣơng pháp thiền để cầu xin cho tất cả mọi ngƣời đƣợc lòng từ ái và thiện chí). Có khi ông ở tại nhà và luyện tập tâm từ cho sự ổn định của đất nƣớc. Trong những hoàn cảnh nhƣ thế này, tâm hồn của Sayagyi dịu dàng nhƣ một cánh hoa hồng.

Nhƣng tâm hồn ông cũng có thể cứng rắn nhƣ kim cƣơng. Trong thời kì khủng hoảng này, xảy ra sự kiện chính quyền phải cầu viện một nƣớc lân bang. Nƣớc này rất thân thiện và đồng ý trợ giúp Myanma, nhƣng những vũ khí viện trợ cho Myanma phải chuyên chở bằng đƣờng hàng không, mà chính quyền Myanma lại không đủ phƣơng tiện chuyên chở hàng không. Các máy bay cần dùng cho mục đích này phải đƣợc cung cấp từ bên ngoài. Ðể đạt đƣợc mục tiêu, chính quyền đã có một quyết định vội vàng không phù hợp với luật pháp của quốc gia.

Lúc bấy giờ U Ba Khin đang là Kế toán trƣởng, và ông phản đối quyết định này vì nó bất hợp pháp. Chính phủ rơi vào tình trạng tiến thoái lƣỡng nan. Thủ tƣớng biết rõ Sayagyi sẽ không khoan nhƣợng khi đụng đến vấn đề nguyên tắc. (Ông luôn luôn khẳng định, “Tôi đƣợc nhà nƣớc trả lƣơng vì một mục đích duy nhất — trông coi để không một đồng xu trong ngân quĩ nhà nƣớc bị sử dụng ngƣợc với luật pháp quốc gia. Tôi đƣợc trả lƣơng để làm điều này!”) Thủ tƣớng rất kính trọng sự ngay thẳng và tinh thần bổn phận của Sayagyi. Nhƣng hoàn cảnh bấy giờ quá tế nhị. Vì vậy, ông cho mời Sayagyi đến thảo luận riêng với ông, và ông nói: “Chúng ta đang rất cần đƣa số khí giới này về, và cần phải chi tiêu vào việc chuyên chở bằng máy bay. Vậy ông thử cho chúng tôi biết phải làm việc này thế nào cho hợp pháp.” Sayagyi đã đề nghị một giải pháp, và chính phủ đã theo lời khuyên của ông để không sử dụng một phƣơng tiện sai trái cho một hành động đúng đắn. Cuộc khủng hoảng còn tiếp tục một thời gian, nhƣng sau cùng các phe phái nổi loạn đã bị lực lƣợng chính phủ đánh bại dần dần trên khắp đất nƣớc, trừ một vài nhóm ở những vùng đồi núi xa xôi.

-ooOoo-

In Wartime, as in Peacetime, a Man of Integrity

During the month of February, 1942, the invading Japanese Imperial Army had occupied Yangon and was advancing toward Mandalay, a city in central Myanmar. The Japanese Air Force started an aerial bombardment of the city, in which the railway station was destroyed.

At this time Sayagyi was stationed in Mandalay as Accounts Officer of the railways, with responsibility for whatever funds were kept in cash. After the bombardment was over, he went to the ruined station, searched through the debris, and found still intact the iron safe in which the cash was kept. Having the key with him, he opened the safe and removed the cash contents—a substantial sum of money.

Now what to do with this money? U Ba Khin was at a loss. The British authorities had already fled in retreat from the fast-approaching Japanese. Mandalay at that moment was a “no man’s land” between the two armies—a city without any government. It would have been very easy for Sayagyi to take the money for himself,

without anyone’s being the wiser. After all, what right did the defeated, fleeing British colonial government have to this money? It could be construed as a patriotic action to deprive them of it. Moreover, Sayagyi had great need of money at that time, since his young daughter was seriously ill, and his expenses were therefore unusually heavy, severely taxing his means. U Ba Khin, however, could not even conceive of misappropriating government funds for his own use. It was his duty, he decided, to hand over the cash to his superior officers even though they were fleeing from the country.

From Mandalay the British had fled helter-skelter in every direction. The railway officers had retreated first to Maymyo, in hopes of making their way from there to Nationalist China and thence by plane to India. Sayagyi did not know whether he would be able to catch up with them in their flight. Nevertheless, he had to make the attempt. He hired a jeep taxi and made the three-hour journey to Maymyo. On his arrival, he found that the British were still in that city. He sought out his superior officer and handed over the cash to him, breathing a sigh of relief at having been able to discharge his duty.

Only then did Sayagyi ask, “And now, sir, may I receive my salary for this month, and my travelling expenses to here?” This was U Ba Khin, a man of perfect integrity, of incorruptible morality, of Dhamma.

Dhamma Transforms a Government Department

By introducing the practice of Vipassana meditation to the officers and staff of the Burmese Accountant General’s office, Sayagyi U Ba Khin had brought about remarkable improvements in that government department. The Prime Minister at that time, U Nu, was an honest man and wished the entire administration of the country to be similarly freed from corruption and inefficiency. One of the most important government offices, the State Agricultural Marketing Board, was in poor shape. This organization was responsible for purchasing paddy (a type of rice)—as well as other produce—from the farmers, and arranging for milling the rice and exporting the bulk of it.

In colonial times, the entire rice export business had been in the hands of British and Indian traders. After Myanmar’s independence, the Board had taken over this function. Most of its officers and staff had little prior experience. Although the margin of profit in the trade was huge, somehow the Board suffered a chronic deficit.

There was no proper system of accounting; inefficiency and corruption were rampant. The Board officials, in collusion with the rice millers and foreign buyers, were embezzling huge amounts of money from the state. Additionally, great losses occurred due to poor storage practices and inefficient loading and transport.

The Prime Minister set up a committee of inquiry headed by Sayagyi to thoroughly investigate the affairs of the Board. The report of this committee unflinchingly exposed the entire net of corruption and inefficiency. Determined to take strong action—even though it meant overriding the opposition of traders and some of the politicians of his own party who were involved in the corruption—the Prime Minister requested U Ba Khin to take the post of Deputy Chairman of the Board. Sayagyi, however, was hesitant to undertake the responsibility of reforming the Board unless he could have clear authority to undertake any necessary measures. Understanding the problem, the Prime Minister instead appointed Sayagyi to chairmanship of the Marketing Board, a cabinet-level position normally held by the Minister of Commerce. It was generally known that this position afforded great political leverage—and now it was being given to an honest civil servant!

When the intended appointment was announced, the officers of the department became nervous that the man who had exposed their malpractices and inefficiencies was now to become their superior. They declared that they would go on strike if the appointment was confirmed. The Prime Minister replied that he would not reconsider, since he knew that only U Ba Khin could undertake the job. In retaliation, the officers carried out their threat. So it was that Sayagyi took up his appointment in an office where the executive staff was striking while the clerical and blue collar workers continued to work as usual.

Sayagyi remained firm despite the unreasonable demands of the strikers. He continued the work of administration with just the clerical staff. After several weeks, the strikers, realizing that Sayagyi was not going to submit to their pressure, capitulated unconditionally and returned to their posts.

Having established his authority, Sayagyi now began, with great love and compassion, to change the entire atmosphere of the Board and its workings. Many of the officers actually joined courses of Vipassana under his guidance. In the two years that Sayagyi held the Chairmanship, the Board attained record levels in export and profit; efficiency in minimizing losses reached an all-time high.

It was common practice for the officers and even the Chairman of the Marketing Board to amass fortunes in various illegal ways during their terms of office. But U Ba Khin could never indulge in such practices. To forestall attempts to influence him, he refused to meet any traders or millers except on official business, and then only in his office and not his residence.

On one occasion, a certain merchant had submitted to the Board a bid to supply a huge quantity of burlap bags. According to the usual custom, this man was prepared to supplement his bid with a private “contribution” to an important Board member. Wanting to assure his success, he decided to approach the Chairman himself. He arrived at Sayagyi’s house, carrying with him a substantial sum of money as an offer. During the course of their conversation, when the first hint of bribery arose, Sayagyi was visibly shocked and did not hide his contempt for such proceedings. Caught in the act, the businessman hastened to emphasize that the money was not for Sayagyi himself but rather for his meditation center. Making it clear that the meditation center never accepted donations from non-meditators, Sayagyi ordered him out of the house, and told him he should be thankful that the police were not called into this.

As a matter of fact, unbeknownst to the merchant, his bid—the lowest one submitted—had already been accepted by the Board. Since all official requirements for this transaction had already been met, a bribe could be harmlessly accepted without interfering with the interests of the state. In such circumstances, it would be

commonplace for an official to just accept the gratuity “in the flow of the tide” (as such a situation was popularly referred to). Sayagyi might have easily accrued these material benefits, but doing so would have been totally against the moral integrity of such a Dhamma person.

In fact, to thoroughly discourage any attempt to influence him, Sayagyi let it be known that he would not accept even small personal gifts, despite the common practice of such exchanges. Once on his birthday, a subordinate left a gift at Sayagyi’s house when he was not at home: a silk longyi, a wraparound sarong typically worn by both men and women. The next day Sayagyi brought the present

to the office. At the end of the working day, he called a staff meeting. To the mortification of the staff member who had left it for him, Sayagyi berated him publicly for so blatantly disregarding his explicit orders. He then put the longyi up for auction and gave the proceeds to the staff welfare fund. On another occasion, he took similar action on being given a basket of fruit, so careful was he not to allow anyone to try to influence him by bribes whether large or small.

Such was U Ba Khin—a man of principles so strong that nothing could cause him to waver. His determination to establish an example of how an honest official works brought him up against many of the practices common at the time in the administration. Yet for him the perfection of morality and his commitment to Dhamma were surpassed by no other consideration.

Soft as a Rose Petal, Hard as a Diamond

A saintly person, who is full of love and compassion, has a heart that is soft, like the petal of a rose. But when it comes to his duty, he becomes hard like a diamond. Both of these qualities manifested in Sayagyi’s life from time to time. A few of the many incidents illustrating this are included here.

When Myanmar attained independence from Britain in 1948, the newly-formed national government faced an immediate crisis. Throughout the country, followers of different ideologies were challenging the government: some were communists, some socialists, some provincial secessionist groups. The insurgents had no scarcity of arms and ammunition, because during the Second World War both the Japanese and the Allies had freely distributed arms and ammunition to attract the Burmese youth to their fold. The rebels started fighting on so many fronts that it became impossible

for the newly-formed national army to handle the crisis. Soon the insurgents gained the upper hand, but with their different causes and slogans, a chaotic situation prevailed throughout the country. Each different group with its own unique cause occupied and ruled a different territory.

A time came when the federal government of Myanmar was in fact only the government of the city of Yangon. Soon even this nucleus of control was imperiled when one group of rebels started knocking at the door of the city, occupying a village ten to twelve miles away. There was no rule of law anywhere in the country; the continued existence of the federal government was hanging in the balance. If the government of Yangon fell, the Union of Myanmar would disintegrate into competing factions. The government was distressed, the army was distressed—but what could be done? There seemed to be no way out.

Sayagyi was deeply devoted to his country, and wished peace, harmony and prosperity for Myanmar, but what could he do? His only strength was in the Dhamma. So at times he would go to the residence of the Prime Minister and practice mett± (meditation of goodwill and compassion for all). At other times in his own home, he would generate deep metta for the security of his country. In a situation such as this, Sayagyi’s heart was very soft, like the petal of a rose.

But it could also become hard as a diamond. It so happened that during the same crisis, the government appealed to a neighboring country for assistance. This friendly country agreed to come to Myanmar’s aid, but whatever items were to be given had to be transported by air, and the government of Myanmar did not have adequate air transport. The airplanes required for the purpose would have to be procured outside the country. To succeed in this plan, the government made a hurried decision which did not fall within the framework of the country’s laws.

At that time U Ba Khin was the Accountant General, and he declared the decision to be illegal. The government was now in a dilemma. The Prime Minister knew very well that Sayagyi would not compromise where principles were concerned. (Sayagyi always asserted: “I get my pay for one purpose only—to see that not a single penny of government funds should be used in a way which is contrary to the law. I am paid for this!”) The Prime Minister had great respect for Sayagyi’s integrity, his adherence to duty. But the situation was very delicate. He therefore called Sayagyi for a private

discussion, and told him: “We have to bring these provisions, and we must make an expenditure for the air transportation. Now, tell us how to do this in a legal way.” Sayagyi found a suitable solution, and the government followed his advice to save itself from using a wrong means for a right action.

The crisis continued until eventually the rebel groups, one after the other, were overpowered by the national army and defeated in most of the country, except for the remote mountainous areas. The government then started giving more importance to social programs for the improvement of the country. Thanks to the diligence of the

community of monks, there was a high rate of basic literacy throughout most of Myanmar, except for some of the hill tribes; but higher education was lacking. The Prime Minister took it upon himself to address this situation. In a large public gathering, he announced a strategy to implement adult education throughout the country, and he authorized a large sum of money for this purpose to be given immediately to the ministry concerned.

Sayagyi was fully sympathetic to the virtues of the plan, but he determined that the amount specified did not fit into any portion of the national budget. He therefore objected. The Prime Minister was placed in a very embarrassing situation, but U Ba Khin’s objection was valid: according to law, the announced amount could not be directed to its proposed purpose.

Sayagyi’s judgment was accepted, but the program had already been announced, so something had to be done. The Prime Minister called the officers of the Rangoon Racing Club and requested their cooperation in helping to implement the adult education program.

He suggested that they sponsor a special horse race with high entry fees; whatever money earned would be given as a donation to the noble cause. Who could refuse the Prime Minister’s request? The Racing Club agreed. All went according to plan, and they earned a huge amount on the special race.

Once again, a large public meeting was organized, and with great pomp and ceremony, a check for a large amount was presented to the Prime Minister by the officials of the Racing Club. The Prime Minister, in turn, handed the check over to the minister concerned.

After this event, however, the case came before Sayagyi, and again he raised objections. The Prime Minister was in a quandary. It was, after all, a question of his prestige. Why was Sayagyi now stopping the payment of the check? This was not the government’s money; what right did he have to stop it? Sayagyi pointed out that the income from the race included tax for the government. If the government tax was taken out, the rest could go towards supporting the adult education program. The Prime Minister was speechless, but he smiled and accepted U Ba Khin’s decision.

Just as Sayagyi was fearless in disposing his official responsibilities, so he was free from favoritism. The following incident is one amongst many incidents illustrating this trait.

In the Accountant General’s department, one of the junior clerks was also one of Sayagyi’s Vipassana students. This man was very humble, ever willing to lend a helping hand. He was always very happy to serve Sayagyi, and Sayagyi had great paternal love for him. Even paternal love, however, could not become an obstacle to Sayagyi in fulfilling his appointed duty.

It happened that at the end of the year it was time for staff promotions. At the top of the list prepared by the staff was the name of this junior assistant. Because he had the greatest seniority in the department, he was next in line for rightful promotion. If Sayagyi had wanted, he could easily have recommended this promotion, but he did not do so. For him, promotion should not depend only on seniority. It should also take into consideration one’s ability to work efficiently. The assistant, who had many other good qualities, was unfortunately lacking in this area. Sayagyi called him and lovingly explained that if he was able to pass a certain accountancy examination, he would get the promotion. The disciple accepted the advice of his teacher, and it took him two years to study and pass the examination. It was only then that Sayagyi granted the promotion.

There are very few people who are free from fear or favor, or who have a love which is paternal yet detached. Sayagyi had all these qualities. Soft as a rose petal, hard as a diamond. I feel fortunate to have learned Dhamma from such a teacher. I pay my respects, remembering these shining qualities of his.

An Ideal Dhamma Teacher

An Ideal Dhamma Teacher

-By Mr. S. N. Goenka

An important principle of this tradition is that no price can be put on the Dhamma because in fact it is priceless. To earn money by teaching the Dhamma is unethical and completely forbidden. If someone wants to earn money, there are endless business opportunities. But the Dhamma is not a commercial commodity, not something for sale. A businessman makes money by his work and becomes rich; but a teacher of the Dhamma must never amass wealth by charging fees for the teaching. Instead, this tradition strictly follows the Buddha‘s injunction, Dhammena na vaniṃ care— Do not make a business of Dhamma.‖ Anyone who ignores this injunction teaches not Dhamma but its opposite.

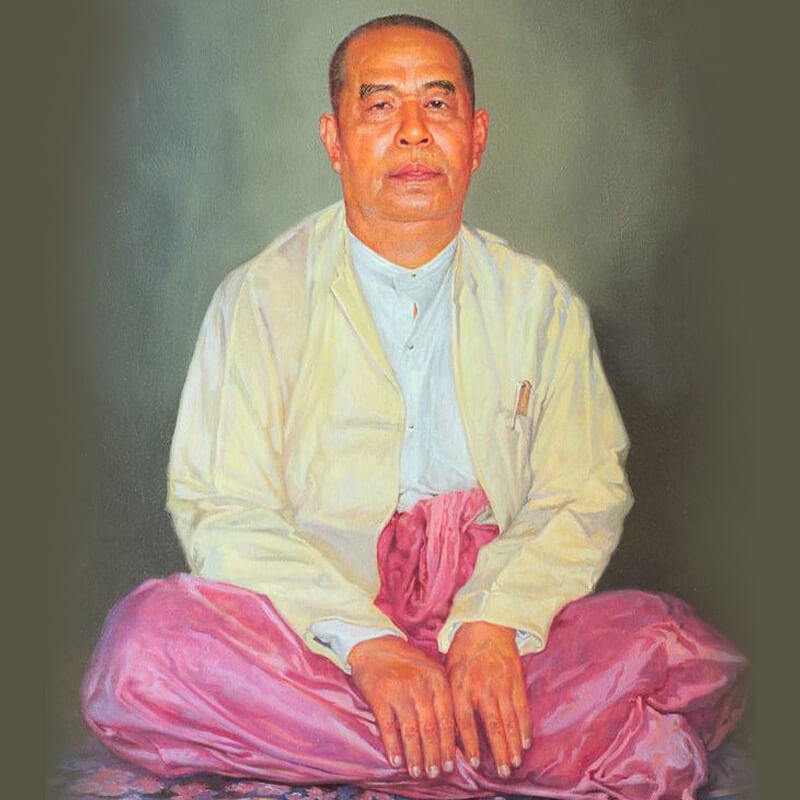

My revered teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin fully lived the ideals of Dhamma. He was a senior member of the civil service, where it was commonplace to make fortunes through fraudulent practices. But Sayagyi was ripened in Dhamma. He worked in this corrupt environment and emerged without any stain on his character.

In the Myanmar of Sayagyi’s day, certain high government posts ensured comfort for the remainder of an ap- pointee’s life, not partic-ularly due to the level of salary, but rather to the pervasive practice of padding all transactions with bribery. No one came out of these offices a poor person. Sayagyi, however, entered his retirement with meagre life savings and no home of his own for his family, since they had lived in Government housing throughout his career. Even though he had worked in as many as four government departments simultaneously, he had accepted only one salary and, of course, avoided all illegal gains.

Wanting to build a house for his children, he asked me to help him arrange for the construction. As work on the house proceeded, we found that 10,000 rupees were lacking for completion. Where was Sayagyi to get this money? He certainly would not ask for it. Since such a sum was so easy for me to give, I suggested this to him. But he refused, insisting that any money from a student isdana (donation) and therefore to be put to proper Dhamma uses. Trying a different angle, I offered to lend him the money, thinking that later I could just tell him to disregard payment. He accepted my offer, and the house was completed.

However, each and every month thereafter when his pension check arrived, he took not one penny of it, but im- mediately passed the whole thing to me. This was very painful for me to accept. These 10,000 rupees meant so little to me, and here each month I had to receive my teacher’s only income. Eventually 5,000 rupees remained to be paid.

During this time, my aunt (who had adopted me as her son and who had been a longtime student of Sayagyi’s) was dying. She had made great progress in her

seven years of meditation with Sayagyi, and he was quite fond of her. Now, it is a custom in the Eastern countries not only to care for one’s parents during their lifetime, but also to remember them by making contributions in their name after death. So as I passed the last days with my mother, I asked her to tell me where she wished me to give this dana.

She said, “Wherever you want.”

I named several hospitals, charitable organizations, and so on. “And where else would you like to donate?” I asked.

When she said that she wanted 5,000 rupees to go to Sayagyi himself, I was delighted. Here was my chance to be relieved of this terrible burden of having to receive money from my teacher. Surely, I thought, Sayagyi would accept the dana as a last wish of a devoted dying student and then be able to use it for repayment of the loan.

As it happened, a few days later Sayagyi was present at the time of her death; he knew that she had died peacefully and consciously, with awareness of anicca at the top of her head. He went around the center telling everyone how her final minutes were filled with Paññā, with anicca. When I informed him of her volition to give him the 5,000 rupees, he was very pleased. “Look,” he said, “she has given these 5,000 rupees as dana,” and he began distributing it to this Dhamma cause and that Dhamma cause! I was so surprised to see my hopes dashed.

Each month thereafter as I received my teacher’s pension check until, at last, the final payment, I was reminded of the high principles of this person who was such an example of moral rectitude in public office.

His determination to establish an example of how an honest official works brought him up against many of the practices common at the time in the administration.

For instance, to thoroughly discourage any attempt to influence him, Sayagyi let it be known that he would not accept even small personal gifts, despite the common practice of such exchanges. Once on his birthday, a subordinate left a gift at Sayagyi’s house when he was not at home. Next day, Sayagyi brought the present to the office. At the end of the working day, he called a staff meeting. To the mortification of the staff member who had left it for him, Sayagyi berated him publicly for so blatantly disregarding his explicit orders. He then put the gift up for auction, and gave the proceeds to the staff welfare fund. On another occasion, he took similar action on being given a basket of fruit; so careful was he not to allow anyone to try to influence him by bribes whether large or small.

Such was U Ba Khin, a man of principles so strong that nothing could cause him to waver. For him, the perfection of slla and his commitment to Dhamma were surpassed by no other consideration.

Having passed through the corridors of power which were rampant with corruption, where fortunes were often easily amassed, here was a singular man of modest means who died with the wealth of his integrity fully intact. Today I remember the high ideals of this great man and I feel inspired. What a rare example he set of fulfilling ethical standards!

(Courtesy: International vipassana Newsletter Vol. 23, No. 2, May, 1996)

Sayagyi U Ba Khin: Truth Triumphant

Sayagyi U Ba Khin: Truth Triumphant

-By Mr. S. N. Goenka

The Buddha was called saccanāma. It was a suitable name for him. The word “mind” is nāma in Pali. Saccanāma, therefore, means one whose mind knows only the truth, nothing but the truth.

Even before my revered teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin came in contact with the Buddha’s teaching of Vipassana meditation, he was a truthful person by nature. He was of outstanding merit from his boyhood. In the year he graduated from secondary school, he stood first among all the students in Myanmar in the matriculation examination. This achievement won him a government scholarship.

Unfortunately, his family could not afford for him to continue his studies. Instead he had to begin work, taking odd jobs. Already he was interested in accountancy, and on his own he read books on the subject and became thoroughly versed in it. With this background, he was able to find a job as a clerk in the Office of the Accountant General. His happiness knew no bounds.

After some time he went to learn Vipassana from Saya Thet Gyi, and advanced far even in his first course. On returning to work, he was informed that he had been promoted to the post of superintendent. From his first day as a clerk in the office, he had seen that corruption was rampant. Almost all employees, senior or junior, took bribes. But this truthful man had never done so. Now that he had become a Vipassana meditator, accepting a bribe was totally out of the question.

In 1942, Japan attacked Myanmar, and its aerial bombers destroyed Mandalay Railway Station, where U Ba Khin was then the Accounts Officer. He saw that the station’s safe had not been damaged in the bombing raid. The senior railway officers, who were British, were intent on escaping to India. If U Ba Khin had kept the government money for himself, no one would have known about it. But he unlocked the safe, took out the contents, drove two hours by car and handed over the money to the senior most railway officer, who was on the way to the airport. U Ba Khin had need of money at that time because his daughter was ill. But he did not want to keep even a penny that belonged to others. Such a selfless person, free of craving, was Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

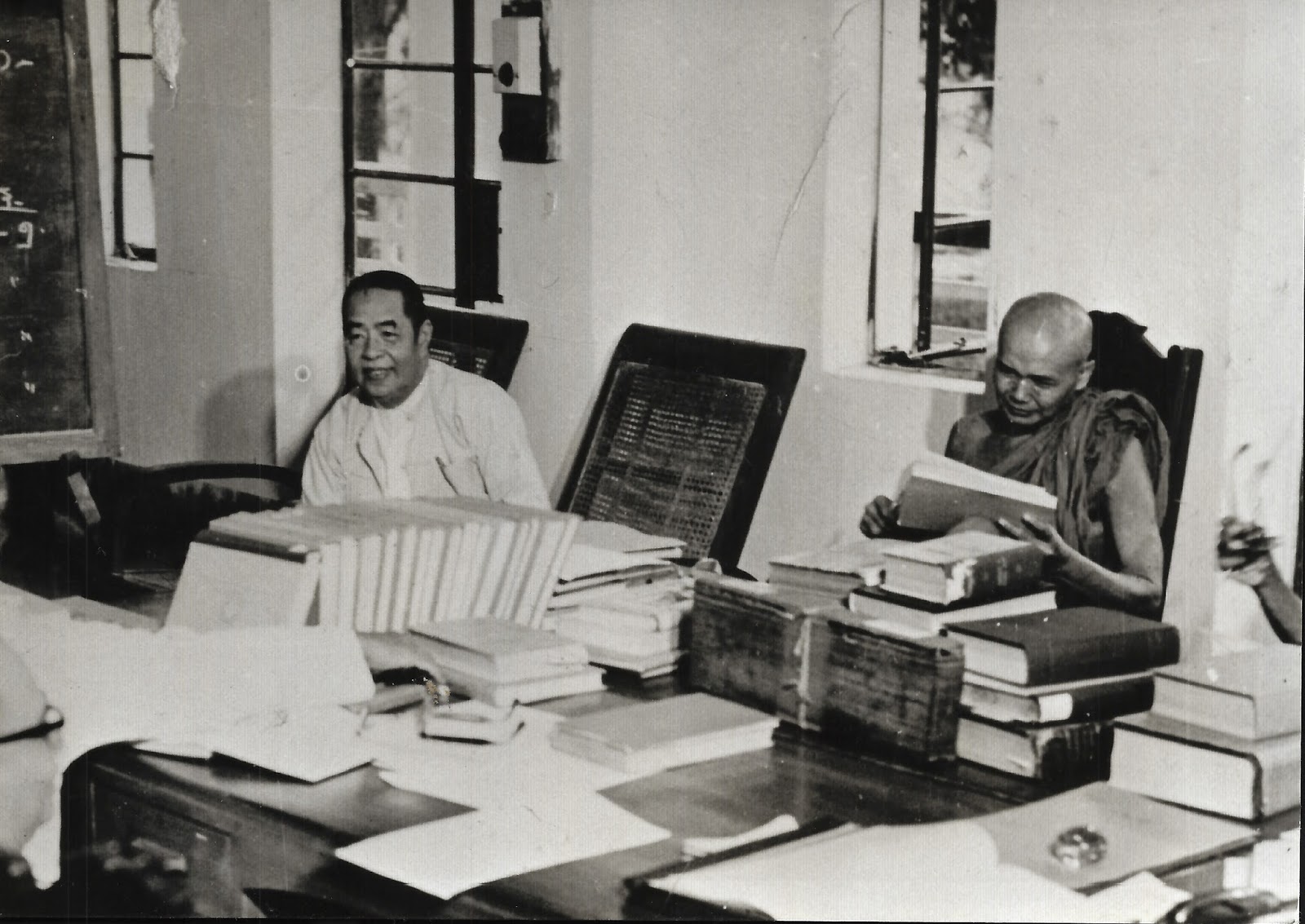

After the war Myanmar became independent, and the new government appointed U Ba Khin Accountant General. He was fully aware that bribe taking was commonplace in his office. As head of the office, he decided to end this unethical practice. But he also knew that someone who takes bribes never changes for the better merely under threat of punishment. He therefore persuaded employees to practice Vipassana.

He set aside a large hall in his office as a Vipassana centre for the use of employees. There he started conducting Vipassana courses. The result was a noticeable change as the employees stopped taking bribes. Gradually the whole atmosphere of the Accountant General’s Office changed, attracting widespread praise.

The Prime Minister at that time was a very honest man. He had tried to introduce reforms but without success. Now he sent for U Ba Khin and asked him to take responsibility for three other departments in addition to his own. U Ba Khin agreed, giving part of his workday to this task. A truthful man is necessarily a man of action. His capacity to work increases. U Ba Khin began to promptly settle pending files at the other three departments. At the same time he inspired the employees to practice Vipassana.

According to government rules, U Ba Khin was entitled to a full salary from his home department and an additional one fourth of his salary from each of the three other departments that he headed. But this truthful man would not accept the extra pay. He said that he worked only eight hours a day, and it did not matter whether he spent the time in his home department or another one. He saw no reason to receive more money.

In those days, the State Agricultural Marketing Board had a monopoly on purchases and sales of rice, Myanmar’s leading crop and a major export. The Board would sell the rice to foreign governments at four times the price it paid to Myanmar farmers, but its balance sheet still showed huge losses because of fraudulent practices. To reform the Board, the Prime Minister asked the truthful U Ba Khin to become its head. U Ba Khin accepted the post on condition that no one interfere with his decisions and that he be allowed to run the Board independently. The Prime Minister agreed but the response was panic in the office of the Board. Fearing to be exposed as corrupt, the senior officer called on all workers to strike.

U Ba Khin was free from animosity, fearless and a steadfast man of action. With staff from the Office of the Accountant General, he began to work through the many pending files of the Board. He remained calm. Finally, after three months the strikers came to him, begged forgiveness and said they were willing to return to work. But U Ba Khin did not accept their offer. He said that before returning, each employee must complete a Vipassana course. By then, U Ba Khin had established the International Meditation Centre in a suburb of Yangon. Practicing Vipassana there, the previously corrupt workers gradually benefited and consequently the nation benefited. The State Agricultural Board began to show a large profit.

After years of successful work, U Ba Khin’s time to retire drew near. But how could the government afford to lose such an honest officer? Instead, year after year it extended his service. This continued for 12 years. Finally U Ba Khin insisted on stepping down so that he could devote the rest of his life to the service of Dhamma.

As a senior official, he had had the use of a government car and driver. The government was happy for him to continue to have this perk of office, but U Ba Khin would not hear of it. Instead, whenever he needed to be driven somewhere, he would inform us and my son Sri Prakash, whom he loved just like his own son, would take him. Although busy with school studies, Sri Prakash was happy to be of service because he was devoted to Sayagyi and had sat eight ten-day courses with Sayagyi. Almost all the members of my family, including my elder brother Bal Krishna, had sat courses with Sayagyi and derived great benefit.

It is because of my meritorious deeds of past lives that I came in contact with such a virtuous and saintly person. I received the gift of Dhamma from him. He made me grow and develop in both the theoretical and practical aspects of Dhamma for 14 years. I suppose he showed me so much affection because of our association in past lives. I benefited greatly from his guidance. When the government of Myanmar issued me a passport to go to India, I was pleased but Sayagyi was far more delighted than I.

Everyone knew that he had unbounded love for India. Myanmar had received from that country the technique of Vipassana as well as the Tipitaka containing the words of the Buddha, but both had been completely lost in the land of their origin. We heard Sayagyi say again and again that India had given the priceless gift of Vipassana to Myanmar, which therefore was greatly in India’s debt, and that now was the time to make repayment, which was badly needed by India. He also used to say, “I will repay the debt.” And again and again Sayagyi would say, “The clock of Vipassana has struck. I need to go to India as soon as possible to revive Vipassana, the great technique of meditation discovered by the Buddha.” But the government of Myanmar had stringent travel restrictions and he could not obtain a passport.

Therefore, when I received permission to travel, he said that I would repay the debt on his behalf. In June 1969, Sayagyi appointed me his representative and an Ācāriya (teacher) to teach Vipassana in the old tradition and said to me, “You will fulfill all that I wanted to do.” I was taken aback to hear this. How can an ordinary man like me fulfill the Dhamma mission of this great person! Knowing what was in my mind, he said to me firmly, “You are not going alone. I am going with you. Dhamma is going with you.”

Although I felt hesitant, his words reassured me and I came to India. I had doubts that people there would help me with this Himalayan task. All the members of my family were deeply committed to a different spiritual path. How could I hope that they would help with the spread of Vipassana? When I prepared a list of my friends and acquaintances in the whole of India, I saw that the number did not reach even a hundred. How was I to find help to carry out the great task entrusted to me?

But somehow Sayagyi’s confidence proved warranted. The Dhamma worked, and only 12 days after I arrived in India, the first course of Vipassana began. Since then the Ganges of Dhamma has flowed without interruption. Now it flows not only in India but around the world.

In the beginning, the courses were all in Hindi since I felt I lacked sufficient fluency in English. For this reason I refused a request to give a course in Dalhousie, with discourses in English. The disappointed students contacted Sayagyi, who phoned from Myanmar to chide me. He said, “You are not conducting courses, I am conducting them. Dhamma is conducting them. Go and teach in English.” Obediently, I conducted the first course in English in 1971. I was myself greatly surprised to find that it was easy for me to give the evening discourse in fluent English.

There were many such occasions making it clear that not I but Sayagyi was teaching Vipassana. How can I forget his generosity to me? My devotion and gratitude to him have grown day by day. I am now 88. More than 1.5 million people have learned Vipassana and benefited from it. When they meet or write to me, they express their gratitude to me with deep emotion. But I think to myself, “Why are they grateful to me? They have received Dhamma from Sayagyi. I am simply a Dhamma messenger sent by him. I distribute only what I have received from him. It is through his kindness that they have learned Vipassana.”

When this happens, I recall the words of a traditional Indian song from the state of Haryana:

‘O God! Who can fathom your wonderful power?

-You impoverish the rich and shower wealth on the poor’.

I do not know whether there is any god who showers wealth on the poor. But definitely there was a man affluent with Dhamma who showered his wealth on a poor man like me. Material wealth is sure to be lost sooner or later. But the immeasurable wealth of Dhamma never decreases, even though one distributes it throughout one’s life. Instead, it keeps increasing.

It is he who gave me Dhamma, it is he who is distributing it through me. Again I recall a song, this time from Rajasthan:

“It is oil and wick that burn, but the credit is given to the lamp.”

When a flame arises from a wick soaked with oil, light is produced. But people say, “See, the lamp is burning and its light is spreading.” In fact the lamp is simply a receptacle for the oil and wick. It does not burn or produce light. Similarly I simply convey the teachings of Sayagyi. The true Dhamma within me was given by him, and that is what produces light all around. For this reason, those who say that I am distributing the light of wisdom are missing the truth. Sayagyi’s light—the light of the true Dhamma he taught to me—is radiating through me and spreading far and wide.

May the men and women who have learned Vipassana, and all who will learn it in the coming years, feel infinite devotion and gratitude to Sayagyi.

In ancient times the Emperor Asoka sent Sona and Uttara as Dhamma emissaries to Myanmar. People there eventually forgot the names of these two messengers, but they have never forgotten Asoka. After the Buddha himself, Asoka is their Dhamma king, the emperor of their hearts, and it is natural to feel grateful to him. In the same way Vipassana meditators should always remain grateful to the Buddha and to Dhamma Teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin, who sent this beneficent meditation back to India and from there around the world. If they know nothing about the Buddha and this saint of modern times, if they do not remember both, they are lacking in gratitude.

It is important to ensure that their memory will survive for 2,000 years and that people will feel grateful to them. And that is the reason for constructing the Global Vipassana Pagoda in Mumbai, a monument of peace and harmony. Whenever people see this Pagoda, they will recall the Buddha and this modern saint Sayagyi U Ba Khin who very compassionately made Vipassana meditation available to the world. Truly, that is cause for gratitude.

I am reminded of a verse by the poet Rahim. In his lifetime he was the commander of the Emperor Akbar’s army and enjoyed immense wealth. He was generous by nature, and every day he would sit on the terrace of his house, distributing coins to the poor. But while doing this, he kept his eyes downcast and head bowed. When people asked him why, he replied:

“The giver is someone else. He gives day after day.

-Lest people mistake me for him, I lower my eyes and bow my head”.

By these words Rahim meant, “People mistakenly think I am the giver, when in fact it is God.”

Every day new meditators are joining Vipassana courses and new meditation centres are coming up. These continue spreading the light given to me by my revered Teacher. They feel gratitude for the gift of Dhamma; but the gratitude should be to the givers of this gift: the Fully Enlightened One and the great Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

Do not forget to feel and express gratitude to them. This is my Dhamma message on this auspicious day of Guru Purnima.